Stencl in Yiddish magazine ‘In geveb’

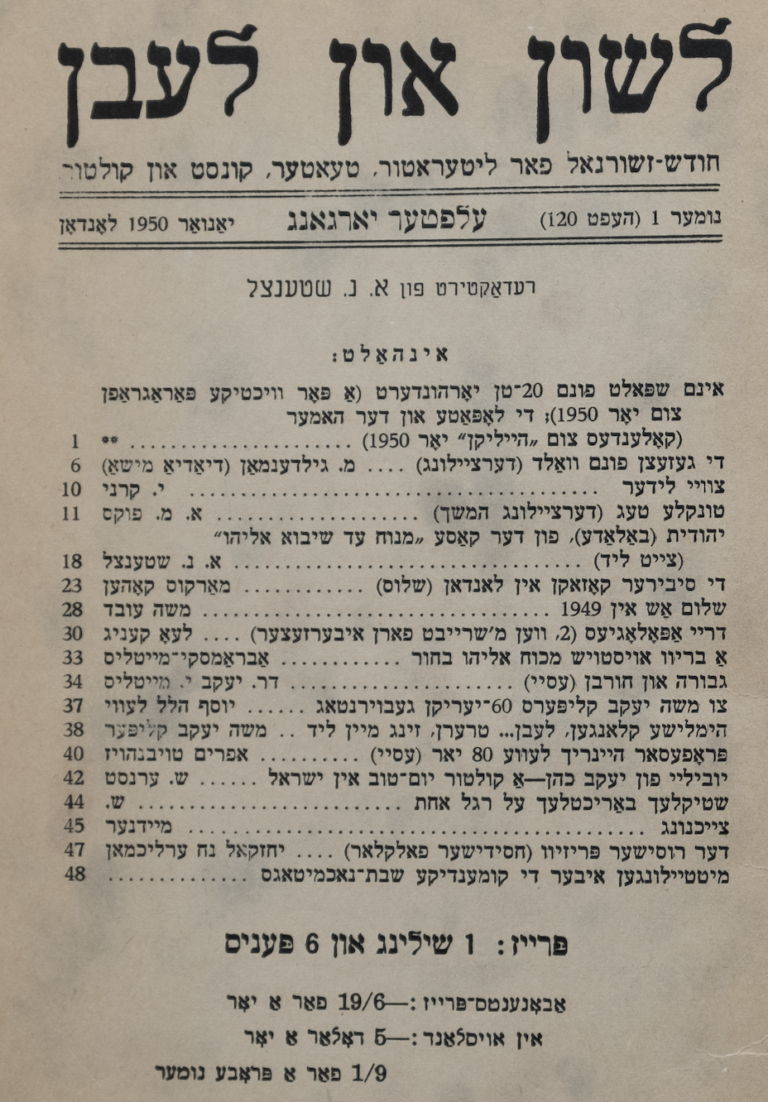

In 2024 Rachel Lichtenstein was invited by the international online Yiddish magazine In geveb to write an article about her ongoing research into the Yiddish poet Stencl, which explores the influence of childhood memory on the project, features the Yiddish residency and details of her forthcoming book The Prince of Whitechapel (William Collins, 2026). You can read some of the article here or the full article here.

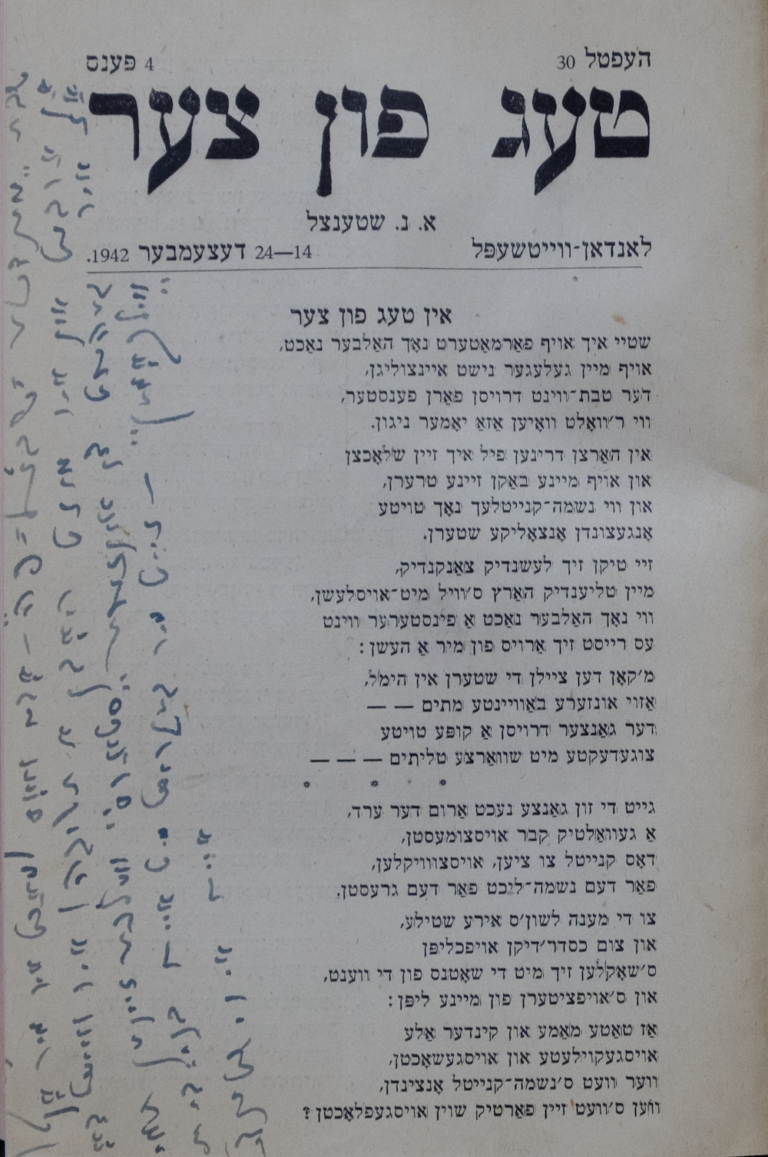

Avrom-Nokhem Shtentsl [Abraham Nahum Stencl] best known as A.N. Stencl (1897–1983) was a Yiddish poet and writer, from a noble Hasidic lineage, who grew up in a small mining town in Russian-occupied Poland. He fled that world in 1919 after receiving his military call up papers then wandered around Europe for some years writing poetry. In 1921 he entered Berlin illegally then lived a bohemian life there until 1936. He published extensively and started a Yiddish literary society during Nazi occupation with Dora Diamant, known as Kafka’s widow. In November 1936 Stencl arrived in London as a stateless refugee and soon settled in the heart of the Yiddish speaking Jewish quarter of Whitechapel, which he affectionately called his “Jerusalem of Britain.” His poems were strongly inspired by observing the busy streets of Whitechapel and the characters in the Jewish cafes, markets, and theatres. He lived there for the rest of his life championing Yiddish language and life.

I have been fascinated by this legendary Yiddish writer since first hearing stories about him as a child from my paternal grandparents, Malka and Gedaliah Lichtenstein. They, like Stencl, were also Polish Jewish emigres who found refuge from persecution in London East End before the war. My grandparents became founding members of the Literarishe shabes-nokhmitiks(Literary Saturday Afternoon) meetings Stencl established there in 1937. These lively gatherings, which later became known as The Friends of Yiddish, were busy noisy events in their heyday, and attracted large crowds of Yiddish speakers from many different backgrounds and communities who were living in East London and beyond at that time. On occasion guest writers came from abroad to read from their works; others performed the great Yiddish classics, sung songs, or discussed politics. Post war as the community died or moved away, the meetings got smaller and smaller, but Stencl never gave up and kept the group running, even if only one person came along. Stencl died in 1983 soon after collapsing penniless, dressed like a beggar and alone on the streets of Whitechapel.

In the same issue of the magazine there is a wonderful translation of Stencl’s Berlin memoirs by Jake Schneider here.